|

One of the most familiar sights in our country’s religious landscape is the Jhandi or the bamboo pole carrying flags of different colours .

Our East Indian Ancestors of Hindu faith who embarked on our shores 175 years ago brought with them the practice of hoisting and planting triangular flags placed on bamboo near homes and temples after the performance of a pooja (Hindu worship/ prayers ) . The presence of the jhandi is a sign of protection from evil forces and a sign of the devotee's piety. When planted firmly in the ground if symbolizes an upright human being, deeply rooted in spiritual values, filled with devotion and humility and intelligently making life choices that support a God centered life. Once hoisted the flag is never broken or pulled down , the bamboo lasts a very long time and is also known to grow where it is planted. This in itself is a promise to sustain the spiritual life . It would be interesting to know what the different colours mean. (Source: Virtual Museum of T&T, May 4, 2022)

0 Comments

— the first group Indians arrived in Jamaica as indentured workers.

By 1917, some 36,000 were on the island. On the plantation, the labourers worked five to six days a week for one shilling a day and lived in squalid conditions. Two shillings and six pence were deducted weekly for their rice, flour, dried fish or goat, peas and seasoning rations. They could only leave the plantation if in possession of a permit. If caught without one or if they failed to work because of ill health or any other reason, they faced fines or imprisonment. The terms of indenture could be one to five, with two weeks annual leave. Labourers could be released from their indenture due to illness, physical disability or in the rare case, manumission or commutation, when they paid the unexpired portion of the contract to their employer. When their indentureships were up, they became known as time-expired Indians and were issued certificates of freedom that enabled them free access to any part of the island. Two years later and no earlier, they could apply for repatriation. If they did not do so they became ineligible even though they could only be repatriated after having lived in Jamaica for 10 years. There was always the option to renew their contracts and become "second-term coolies". Few made that choice. Today there is an estimated 80,000 people of Indian origin living in Jamaica. Indian Arrival Day is annually observed on May 10th. (Source: Dominic Kalipersad, May 10, 2022) Patrick Manning was declared elected unopposed as MP for San Fernando East ahead of the May 24 general election.

He did not have to campaign, owing to a decision of the ACDC-DLP coalition to lead a no-vote campaign. The PNM won the remaining 28 seats on election day, and formed the government with all 36 seats in the House of Representatives. At first, Manning was appointed parliamentary secretary in the Office of the Prime Minister. Then, after the death of Prime Minister Dr Eric Williams in March 1981, he was elevated to a full ministerial portfolio in the Cabinet of George Chambers; holding the Industry and Commerce, and Information portfolios, then Energy and Natural Resources. When the PNM lost the General Election in 1986, Manning was one of three PNM candidates who retained their seats. He became the Leader of the Opposition and within two months was elected to the post of Political Leader of the PNM. In 1991, Manning was appointed Prime Minister. He would again be appointed Prime Minister in 2001, 2002, and 2007. Following the loss of the General Election in 2010, Manning resigned as Political Leader of the PNM but continued as a PNM Representative and Parliamentary Representative for the San Fernando East constituency. When the Parliament was dissolved in 2015, Manning, who was 68 years old, had served in the political arena for 44 years. At the time of his retirement he was the longest serving politician in Trinidad and Tobago. Born in San Fernando in 1946, Manning died on July 2, 2016, from Acute Myeloid Leukemia. (Source: Dominic Kalipersad, May 10, 2022) THE Government has put the struggling four-star Tobago hotel, the Magdalena Grand Beach and Golf Resort, up for sale.

This was confirmed in an expression of interest on the Evolving Technologies (eTecK) website on Friday. The request for expressions of interest is for any qualified international operator, investor and/or purchaser for the resort. The entity/entities must have a proven track record to provide a structure to allow for the renovation, repositioning, branding and an overall plan to improve the performance of the resort. The expressions of interest gives prospective parties three options: 1) An internationally branded operator to manage the resort ,or a third-party hotel management operator, with the brand being franchised; 2) Investor for the property – a strategic partner who will provide capital investment and bring the necessary management and branding expertise. 3) Outright purchase of the entire resort. ETecK, which is responsible for the lease operatorship of the resort, had entered into an agreement with an international operator in 2012 to manage the operations and drive revenues and occupancy levels of the hotel since its rebranding and reopening. ETecK oversees capital works on the resort, which comprises 178 rooms and 22 suites. The resort was opened initially as the Tobago Hilton in 2000 and closed in 2008. It was rebranded as the Magdalena Grand Beach and Golf Resort in 2011. (Source; Newsday, April 29, 2022) The University of the West Indies (UWI) announced on Saturday Prof Rose-Marie Belle Antoine as the new principal of the university’s St Augustine campus. The decision was made during the UWI’s University Council meeting on April 29.

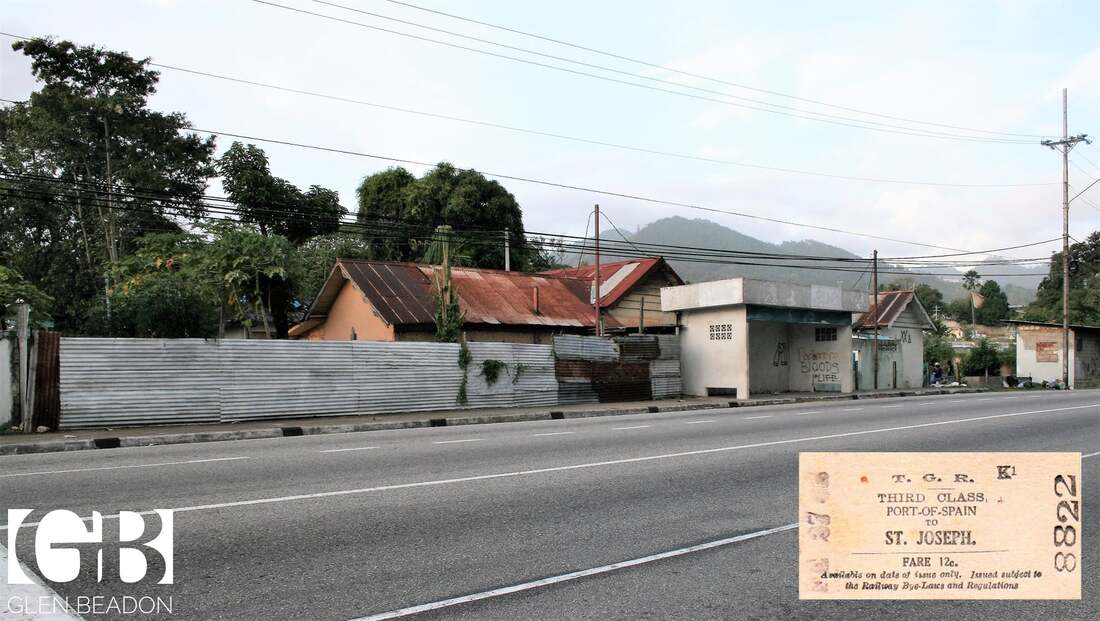

The appointment takes effect on August 1, and Antoine will replace outgoing principal Prof Brian Copeland and become the first woman to hold the post. The UWI’s website states Antoine is a Cambridge and Oxford scholar who holds a doctorate from Oxford University in offshore financial law. Antoine started her journey with the UWI as a temporary law lecturer at the Cave Hill campus in 1989 and then became a lecturer in 1991. Since then, she has served in several high-ranking positions at UWI including law faculty dean and pro vice-chancellor of the Board for Graduate Studies and Research. During her time as law faculty dean, Antoine was instrumental in creating the Makandal Daaga Scholarship, which is an equal-opportunity scholarship aiming to support law students who are outstanding in and out of the classroom. Contacted for comment, Antoine noted Copeland was still principal until her appointment takes effect. Until then, Antoine said, “I would like to give the incumbent some courtesy, so I prefer to comment later. Thanks for reaching out.” But senior lecturer at the UWI’s Institute for Gender and Development Studies (IGDS) Dr Gabrielle Hosein told Sunday Newsday Antoine’s appointment was a step in the right direction. “Over the last decades, there has been a slow erosion of male dominance in UWI’s administrative hierarchy, and Prof Belle Antoine’s appointment as principal is another, significant crack in that old glass ceiling following a number of women, such as Prof Rhoda Reddock, holding the post of deputy principal.” Pointing out Antoine has been an ally of the IGDS, Hosein said she has an excellent track record of inclusive leadership with the unwavering support of human rights and social justice efforts relating to LGBTI non-discrimination, administrative and carceral injustice, marijuana decriminalisation and rights for people with disabilities. “We welcome a UWI principal with such an outstanding record of challenging inequity and exclusion and their intersections with patriarchal and other inequities. “We are confident about her capacity to inspire and to draw the resources of the region toward strengthening the UWI and its capacity to transform the region.” Outside of her work with the UWI, Antoine has served as president of the Organization of American States Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, where she has also been the rapporteur for Persons of African Descent and rapporteur for Indigenous Peoples. As chairman of Caricom's marijuana commission, Antoine has been an advocate for the decriminalisation of marijuana and the creation of a sustainable cannabis industry. She also currently serves as president of the Family Planning Association. The association’s executive director Ava Rampersad described Antoine as a down-to-earth, committed leader who is particularly passionate about the development of young people. Rampersad said, “She is firm when she needs to be firm, she is very innovative and open to ideas. “Once you are able to approach her from a perspective of coming with your evidence to say something, she would definitely support you.” She said Antoine is someone who operates from a place of integrity. “It is no surprise someone with that calibre would be appointed as the principal of the UWI. “We at the association are very proud of her. We are honoured by her accolades, and we continue to support her in her endeavours.” Former principals of UWI St Augustine campus include Prof Clement Sankat (2008-2016), former MP Dr Bhoendradatt Tewarie (2001-2007), Prof Compton Bourne (1996-2001), former president George Maxwell Richards (1985-1996), Prof Lloyd Braithwaite (1969-1984), Sir Dudley Huggins (1963-1969) and Sir Philip Sherlock (1960-1963). (Source: Newsday, May 1, 2022) I took this photograph in 2012 of what remains today of St Joseph Railway Station. The original building although altered and added to over the years since closure, has largely remained intact and today most commuters whiz past it each day, while travelling over the priority bus route, without knowing any its history.

Between each passing bus and the urban sounds now present at this location, it is perhaps still possible to close one’s eyes and imagine the ghosts of a bygone era. Conceivably the cries of the Station Porter, as a train comes to a stop: “St Joseph, this is St Joseph, this train is for San Fernando, all change for the Arima and Sangre Grande line” HISTORY OF ST JOSEPH RAILWAY STATION AND 1880 ROYAL DESCRIPTIONS OF ITS ENVIRONS The railway through St Joseph was built in stages between Port-of-Spain and Arima from 1873 until opening in 1876. The Railway Station building at St Joseph was completed during early October of 1875 and reported as such in the TGR’s fortnightly progress statement on 19 October that same year. The first passenger train into the new station was a trial run on 1 June 1876 and the first official trains began running one month later, on 1 July, when the railway was opened as far as Arouca. The railway opened all the way to Arima on, “Santa Rosa day”, 30 August 1876. Trinidad’s first “Royal Train” ran through St Joseph on 13 January 1880 towards Couva over the new, yet to be opened, Couva Extension railway. That day, their Royal Highnesses Prince Albert and Prince George travelled by train which would have paused momentarily at St Joseph. The Royal Train was drawn by Locomotive No.7 and apart from their Royal Highnesses, the train carried His Excellency the Governor, Sir Henry Irving and a party of invited guests. A brief account of the arrival at Couva is recorded in the book “The Cruise of Her Majesty's Ship "Bacchante": 1879-1882 where it is written: "Went in a special train under the charge of Mr. Tanner (Director of Public Works) and Mr. Marryatt by San Josef to Couvas, through woods and clearings and sugar plantations”. A few days later, on 17 January, the two Royal Princes visited St Joseph by another Royal Train where they recorded this fascinating account (note spelling as per original account): “There was to have been a cricket-match between the “Bacchantes” and the Trinidad club, but it had been so wet in the night that it had to be given up. At 11.30 A.M. started in the train for a ten miles run to San Josef, the old capital of the island, and visited Mr. Giuseppi, senior, where we saw the sugar-cane mill, which was set working this morning: the season has been so wet or it would naturally have been at work some weeks ago. We saw the canes being cut by the negroes with their long cutlasses, stripped, piled in the carts, brought into the mill, pressed, the juice run through, then boiled and skimmed. Within twenty-four hours of their being cut the canes must be pressed under a wheel, and the liquid runs off into a trough. It looks like muddy water; it is collected in tanks and clarified with cow's blood or sulphuric acid, as it simmers over the fire. When it ferments they cease to boil it and put in lime, half an ounce to 100 gallons. Then a thick scum rises to the top and as it cools hardens. This cracks on the surface and the liquid molasses sink to the bottom and become syrup and drain away into another cistern. Then it is put in a pan boiler, or vacuum pan. It then becomes a thick toffee-like substance and is bailed out in pails and thrown into centrifuges, with small quantities of water added to whiten it. The revolving oscillators, things like paddle-wheels, which are turned slowly round in the syrup while it is cooling, cause it to ooze out at the perforations, and the sugar remains behind beautifully dry and white. This is the old way of making sugar; we are to see another at the usine at San Fernando. The remaining molasses is re-boiled and subjected to the same process again; and an inferior sugar is the result. From the treacle which remains at last rum is distilled. The negroes and coolies who are working together in the mill seemed much pleased with our visit. We lunched with Mr. Giuseppi in the old house at Van Saine (Valsayn), the drawing-room of which is the identical one in which the capitulation of the island in February 1797 was signed, on the one side by Don Alonzo Chacon "last and best of the Spanish governors," and by General Abercromby and Admiral Harvey on the other, in which it was stipulated that all " the capitulators and their sons after them should be Englishmen, and counted as such, whether they were French or Spaniards up to that time," and so " I am an Englishman, and proud to be so," said the old gentleman. At lunch too was Mr. Farfan, whose ancestors came to the island in 1640, from one of the oldest families of Spain. It is curious to observe how both the French and Spanish here have become such out-and-out Englishmen: they dread nothing so much as the withdrawal of British rule, which would mean their being absorbed by the republic of Venezuela over the water and falling back into a state of chaos. Trinidad in fact, from its large and varied resources, nearly wholly undeveloped, and its excellent geographical position, bids fair to become, not many years hence, one of the most valuable possessions of the British Crown. The island contains over a million acres of fertile soil; only a tenth part is now cultivated; nearly the whole of the remainder is unappropriated Crown land. The population is less than that of Barbados (though in extent it is three times as large as that island). Commercially, Trinidad takes the lead of British Guiana and every British West Indian colony, without exception. With its teeming soil and salubrious climate, it is capable of supporting over a million inhabitants, ten times the number that it now does. The government is administered by a Governor, with an Executive Council of three members (the colonial secretary, the attorney-general, and the senior military officer). The legislative body is a council of six official and eight unofficial members, all of whom are appointed by the Crown from representative residents, the only object being to get the ablest and most competent advisers on local matters. Sir Arthur Gordon, the late Governor, established a capital system of public education in the colony, and the present Governor has done much for remodelling taxation. Before his time all uncultivated lands were taxed a shilling an acre and the cultivated lands five shillings an acre, which was a premium on keeping the land uncultivated. But now all land, whether cultivated or not, is taxed one shilling an acre, to the great advantage of the colony, as each man has everything to gain by clearing and cultivating his holding. The same principle has been carried out as regards import dues: everything brought to the island was heavily taxed, but the Governor has persuaded his council to sweep away all these dues, and to make the Port of Spain a free port; the only three things that pay duty on entrance are spirits, tobacco, and kerosene oil. Since this ordinance was passed, the commerce of course has greatly increased. The imports have doubled themselves in ten years, and now stand at nearly three millions sterling, the exports at about the same figure. Ultimately all taxation will be reduced, and locomotion by rail will pay for all the expenses of government. Not many English come out here from home, as some capital is required for taking up land as cleared. Yet why should they not, if fond of the tropics? Two hundred acres will cost 200/. to buy; on this say 3,000/. would have to be spent spread over six years, or perhaps even up to the end of the tenth year. This would then (they say) give a net income of 1,400/. for fifty years at least. This is in cacao planting. (Law, Hoiv to Establish and Cultivate an Estate of One Square Mile in Cacao, 1865.) This year the survey of the island has been completed, and the boundaries of the provinces and estates laid down with some approach to accuracy, though out and away the largest portion of the island is still virgin soil or primeval forest. It is to be feared that previous to this there were many forged certificates of land, and much speculation, by unprincipled coloured officials who misbehaved themselves in other ways, but who have been lately routed out. We each planted two trees, one on either side of the road up which Sir Walter Raleigh advanced to San Josef when he landed in the Caroni river. We returned to Port of Spain by train, riding on the engine, and then drove to the new police barracks, over the airy rooms and passages of which we went, and then saw the volunteers, who were drawn up in the quadrangle below, put through their drill, and so home. Walked with Mr. Prestoe through the Botanical Gardens and chose some orchids to be sent to Sandringham, including one called Spirito Santo, the flower of which is exactly like a dove, and another, called the Lady's Slipper, very pretty. Just before we started to go down to the pier we heard the sound of the rain coming from the distance; you can hear it beating on the leaves of the trees on the hillside a long way off, until, as it gradually comes nearer and nearer, it sounds literally just like the roar of a torrent. We drove down to the jetty and caught the six o'clock officers' boat off to the ship. So, ended our visit to Sir Henry Irving. He has been very kind to us, and we have learnt much from him whilst staying this week ashore in his cool and airy house. This evening Captain Lord Charles Scott and the officers gave a dinner to the officers of the 4th Regiment”. St Joseph remained a very busy station on the Trinidad Government Railway throughout its life. Such was the intensity of traffic that complicated operating arrangements had to be adopted between St Joseph and Port-of-Spain. The railway in Trinidad was single line throughout until 1917 when “double track” was installed between Port of Spain and the Eastern Quarry at Lavantille. At this time the lines across the "Dry River" went from one to five lines. The objective behind "double track" (i.e. one line up and another down) was first discussed following a very nasty accident in 1885 when two trains collided between San Juan and St Joseph with loss of life. However, no action was taken until another similar accident occurred in 1915 which remains the most serious to date on the railways of Trinidad. The section of railway between Port of Spain and St Joseph was the busiest on the system as traffic from all lines converged into Port of Spain. Work began in 1917 but was held up during the Great War. Work restarted in 1920 and was finally completed to San Juan in 1923 and onward to St Joseph by 1924. The Trinidad Guardian made the following report on 7 November 1920: “The relaying of the new track and the installment of a double siding have been started by the Railway Authorities under the direct supervision of acting Maintenance Engineer. Mr Eugene Kernahan and his assistant Mr. Roderick Gransaull. The work is being pushed ahead by Mr. C. Newallo, Contractor. Starting from the eastern Quarry on October 8th, the work has been carried to San Juan Station and this has been regarded with satisfaction by the management. There is every indication that at the end of November the relaying will be completed - that is to say, it will be extended to St Joseph Junction”. Apart from the Port of Spain to St Joseph section, all other lines remained single line operation in Trinidad. The TGR built signal boxes (or cabins) along the railway to control traffic at junctions and other strategic locations. The first box was constructed, close to St Joseph, of timber in 1880 when the first part of the Southern Main Line to Couva was opened. This timber structure was replaced by a new "Modern Signal Box" in 1899. The new signal box was a typical British design with concrete base and timber upper storey leaver cabin. From the beginning, although some distance away from (east of) St Joseph railway station, the Junction was called "St Joseph Junction" until 1923 when the name was changed to "Curepe Junction". The reason for the name change was because a new "St Joseph" signal box was constructed at the end of the east platform at St Joseph Railway station in 1924 when double track between Port of Spain and St Joseph was installed. After double track reached St Joseph, the new Signal Box controlled traffic on and off the "double track" section. However, between St Joseph and Curepe, the physical point of the junction, there was in fact two "single lines" running side by side until they diverged just after Curepe halt. Both lines operated as bidirectional lines (or two "single lines") the north line was the Arima Line and the south line was the San Fernando line. The small signal box at Curepe operated signals on both lines and of course controlled the level crossing gates across the Southern main Road by a mechanical apparatus linked to a wheel inside the box. Apart from the Port of Spain to St Joseph section, all other lines remained single line operation in Trinidad. In 1895 Telephonic Communications was established for the first time at St Joseph and it was made available for the Police Department Night Service. On 28 December 1910 the installation of gas lights at the St Joseph Railway Station was completed and the lamps tested that evening, and gave the “utmost satisfaction” according to the Port of Spain Gazette who published the following description: “There are about eleven lamps at this station and they are located on the platform and in the office as well as the waiting rooms. This improved feature of lighting convenience will certainly be a boon to St. Joseph and also to the other railway stations in the local train section where similar work is in progress”. The platforms at “St JOSEPH.” clearly marked on the station board, were set on a curve with a line of around 13 Casuarina trees along the southern side of line. The station building was located on the north side of the line and the compound was totally enclosed by a white timber picket fence from about 1898 onward. There were also water columns for supplying the engines at each end of the platforms. The first railway closures to affect St Joseph occurred on 30 August 1965 when the Southern Main line between St Joseph and every Station/line south of it was closed to all traffic. Soon afterwards the redundant lines at St Joseph became the resting place for old locomotives and rolling stock. The section of line between St Joseph and Tunapuna closed on 7 December 1968, the Tunapuna to Arima section having already closed on Saturday 18 February of 1967. But this was all part of the phased closure of the railway and St Joseph Station, now effectively a “Terminus” for the first time in its history, was to last only 13 more days until 20 December 1968 when the section between San Juan and St Joseph closed, after 92 years of existence. Eight days later the Railway, now under the Public Transport Service Corporation (P.T.S.C.), ran its last passenger train. After closure, all unserviceable locomotives of the Trinidad Government Railways spent their last days languishing at St Joseph in a derelict condition in what became known locally as the “engine graveyard”. Engines and rolling stock were eventually cut up circa 1974/6 when most of the remaining railway assets were scrapped. Today it is almost a miracle that the original building still stands. As in the case of so many railway buildings, modern tenants have become unwitting custodians of what is still a part of Trinidad’s Railway History. Although a far cry from its original guise, the building remains, albeit still with a very uncertain future. St Joseph railway station is now a part of the Trinidad we once knew and at least there is still a bus stop there with its own shelter as can be seen in this photograph. (source: Glen Beadon 4th May 2022. Virtual Museum of T&T)  IF you were born in the community of Garth Road, Princes Town, you probably have heard about the “white man” tomb on Dragon Hill. But you also knew to keep far from it, given the number of jumbies, lagahoos and assorted local ghosts the old folks said were floating around up there, just waiting to follow you home. The hill also had the respect of the cane farmers who ploughed and planted the land, but who left untouched the gravesite in that bamboo grove. And for this we are thankful because it preserved a place that has opened the door to a lost piece of this island’s past. The tomb of concrete, marble, firebricks, and cast iron railing, we discovered, was erected there by Henry Stewart to mark the burial spot of his young wife and two infant children, who all died between 1842 and 1844. Stewart was a resident planter and slaveowner who, when Emancipation was proclaimed in 1834, continued his sugar business using the labour of the indentured Indian immigrants at least until the 1850s when he passes out of the historical records. How Stewart and his doomed family came to live and die in the south Naparimas of Trinidad is a story that time had erased, it appears. Secrets to share But Dragon Hill has other secrets to share, and one of it we found, by accident, mere metres from the Stewart family’s tomb. Hidden behind a tangle of bamboo and reaching through a carpet of dried leaves were broken slabs of blackened stone bearing the name “Jane”. She has been there for almost 200 years. This is why. It starts in the slave labour cotton plantations of North Carolina, USA, in the 1770s during the American Revolutionary War as the patriots fought the British to win their independence from the Crown, while also battling the Loyalists—the Americans who remained faithful to the British Empire. Among those who stayed faithful to King George III was the Williams’ family, who rounded up their slaves and moved to Florida until it became a Spanish territory. So they would move on to the British-owned islands of the Bahamas (north of Cuba) where the Williams brothers were granted lands to start a plantation on an island known as Watlings (now San Salvador). Here, one of the brothers, Burton Williams, amassed more than 300 slaves by the early 1800s. But according to the historical records, Williams claimed that his cotton fields were not prospering in the lean soil of the island, and he couldn’t afford to feed or clothe them for much longer. So in 1821, Williams was granted land in British-owned Trinidad which was then offering inducements to planters to relocate to this island and develop its plantation economy. And over a period of two years, the cargo of 324 human livestock would be shipped across the West Indies by Williams. Our ancestors would have arrived, no doubt, off San Fernando and be marched miles inland across mud roads made impassable during the rains, to their new place of misery. Williamsville, named for him Three estates were developed by Williams for his sons, including Picton (near present day Debe) and Cupar Grange (near Victoria Village, San Fernando). The largest one (300 acres) he named in his honour—Williamsville—which bordered the estate of Garth, south of what is now Princes Town. This area of Savanna Grande, in the fertile south Naparimas, is where Williams settled, building his plantation mansion on a hilltop and overseeing the clearing of the woodland for the planting of sugarcane, and for a cattle farm. Some evidence of this is still found by farmers tilling the surrounding land—bricks, broken pottery, coins and rusted metal of early buildings and sugar works. Evidence of the lives of the Williams’ slaves was also preserved in the records of the British and documented by researchers who found that in Trinidad, they suffered ailments, a poorer diet, lower birth rates and broken family life on a scale much higher than when they lived on their Bahamas island prison. Some of these slaves would be returned to the Bahamas. Of those who remained, some survived to see Emancipation, allowing them to walk off the plantations and start their own settlements (one given the name Hard Bargain after two such settlements in the Bahamas). As for Burton Williams, history records him as living a remarkably long life for the time, but suffering an ultimately miserable demise. As part of the British Empire’s Emancipation compensation to the slaveowners for the loss of their assets, he was paid 851 pounds, eight shillings and one pence for the 80 slaves he owned in the Bahamas. One of his sons, Sir Edward Eyre Williams, ended up becoming a celebrated high court judge in Australia after collecting his Trinidad slave money. Another ended up in a “lunatic asylum” in Kensington, London, so someone else had to claim his share of the spoils, according to the records. As for old man Burton, his Williamsville estate would be acquired by Henry Stewart, who of course would endure his own personal torment. And Burton Williams would return to Watling’s Island (San Salvador) in the Bahamas, never to see Trinidad again. Much has been written about this “Last Loyalist” in a book titled Homeward Bound, A History of the Bahamas Islands (Sandra Riley) where it is recorded, “Reduced from affluence to poverty, Burton Williams eventually outlived all his sons to die at age eighty-three at Watlings in July 1852”, and “Foreseeing that there might be no tools left with which to dig his own grave when he died, he had dug it ahead of time, one of the limestone ridge. His foresight was wise for when this once energetic and rich man died at an advanced age, a Negro servant who only needed to shovel away the light leaf mould from the waiting grave...”. The researchers also suggested that the wife of Burton Williams, whom he married in April 1797, was buried next to him in that grave in San Salvador, which has become a tourist attraction. They were likely wrong about that. What we found buried in the leaves on Dragon Hill is the shattered marble tombstone, sitting atop a bed of bricks, dating most likely to 1822. So we dug it out of the ground, and put the pieces together. The gravestone reads, “Sacred, in the memory of Jane, wife of Burton Williams Esq, died September aged 42”. If you know more about the Williams family, you can contact the writer at [email protected]. (April 20, 2022) Today is my birthday! 28 today… Oups sorry 82!

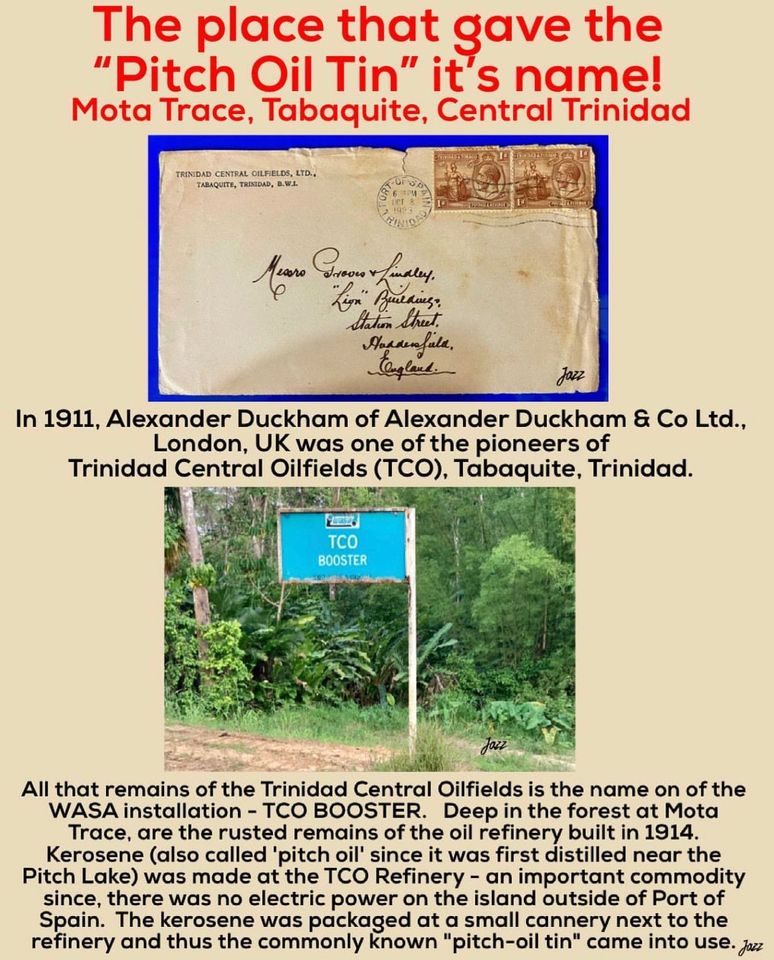

I feel good and I thank god to have kept me strong all these years I miss you my fans all over the world and I think a lot about you, all the time. But don't worry next month you’ll get a taste of me with ‘Watina’ my first song of my new album FOREVER Stay strong be blessed enjoy life! Big bisous to all of you The place that gave the “Pitch Oil Tin” it’s name! - Mota Trace, Tabaquite, Central Trinidad.4/26/2022 Credit Jazad Ali.

In 1911, Alexander Duckham of Alexander Duckham & Co Ltd., London, UK was one of the pioneers of Trinidad Central Oilfields (TCO), Tabaquite, Trinidad. All that remains of the Trinidad Central Oilfields is the name on of the WASA installation - TCO BOOSTER. Deep in the forest at Mota Trace, are the rusted remains of the oil refinery built in 1914. Kerosene (also called 'pitch oil' since it was first distilled near the Pitch Lake) was made at the TCO Refinery - an important commodity since, there was no electric power on the island outside of Port of Spain. The kerosene was packaged at a small cannery next to the refinery and thus the commonly known "pitch-oil tin" came into being. (Source: Virtual Museum of T&T, april 20, 2022) |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

July 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed