|

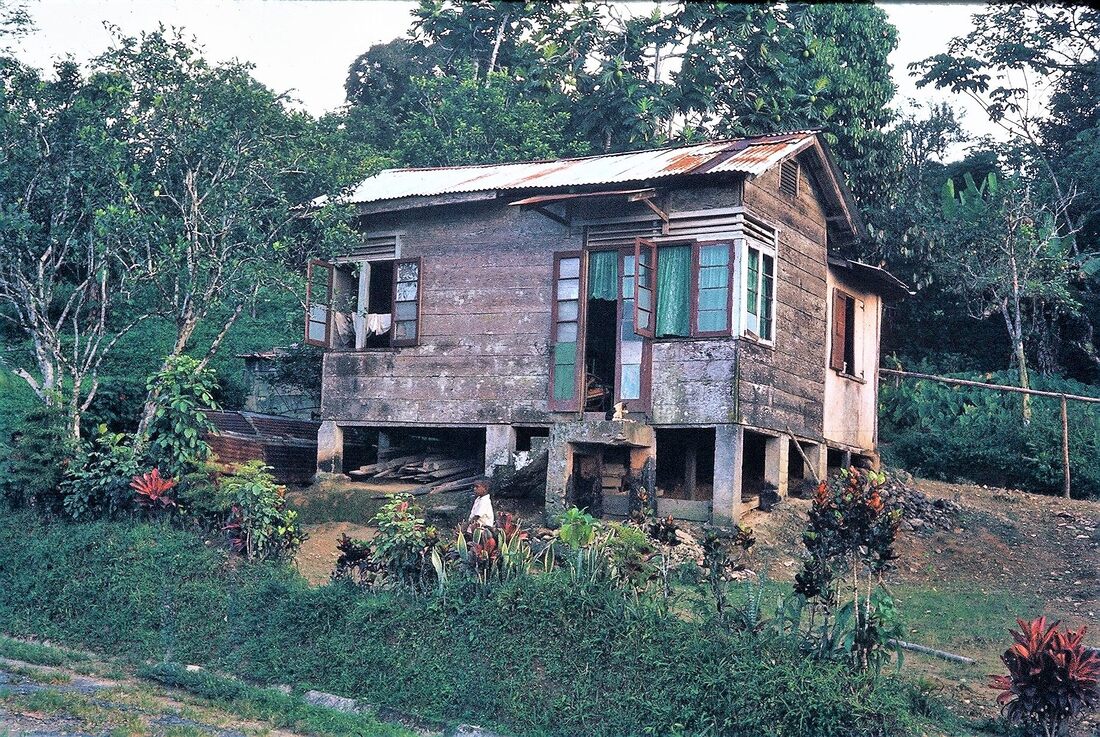

Trinidad and Tobago’s distinctive nineteenth-century architecture survives not only in grand mansions,but in many more modest old houses that linger in our rural landscape creating an architectural blend of the old world and the new .

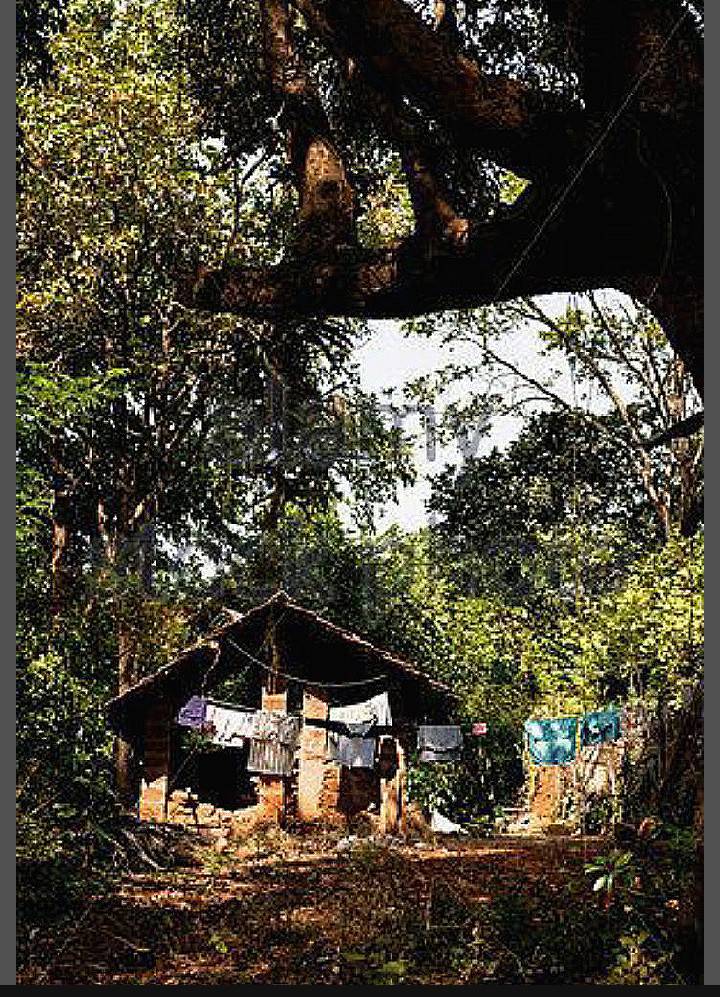

Though rapidly succumbing to the ravages of time, the quaint homes of yesteryear are still very much a part of Trinidad’s landscape. The cosy atmosphere to these old homes that cannot fully be replicated in a modern structure. These homes were built by hand using local timber to provide families a form of shelter from the storms of life. Wooden houses, made of local timber (like the one seen in the attached photo ) were raised off the ground, to protect against floods and provide ventilation, and often featured a pitched roof . The front steps usually led to a gallery that served as a area for the family to gather on afternoons to relax and socialize with each other .In this photo the front steps lead directly to interior of the house. The use of the pillars also increased the living space by providing an “under-the-house” area in which most daily family activities occurred, and the family retreated to the upper section of the home on evenings. Home improvement was always an ongoing activity around the 1960s and 70s , and the first room to increase in size was most notably the kitchen area. These old family homes capture the spirit of those who have been born, raised, and who ended their days within the walls. From the welcoming double-panel doors to the bygone memory of children playing between the raised pillars below, echoes of an era gone still can be heard. What did you home looked like in the decade you were born? Look out for Part 2 of this. (Source: Virtual Museum of TT, June 10, 2023) Photo taken from Angelo Bissessarsingh's Photo Album Collection. House in Grande Rivierre ( 1970)

0 Comments

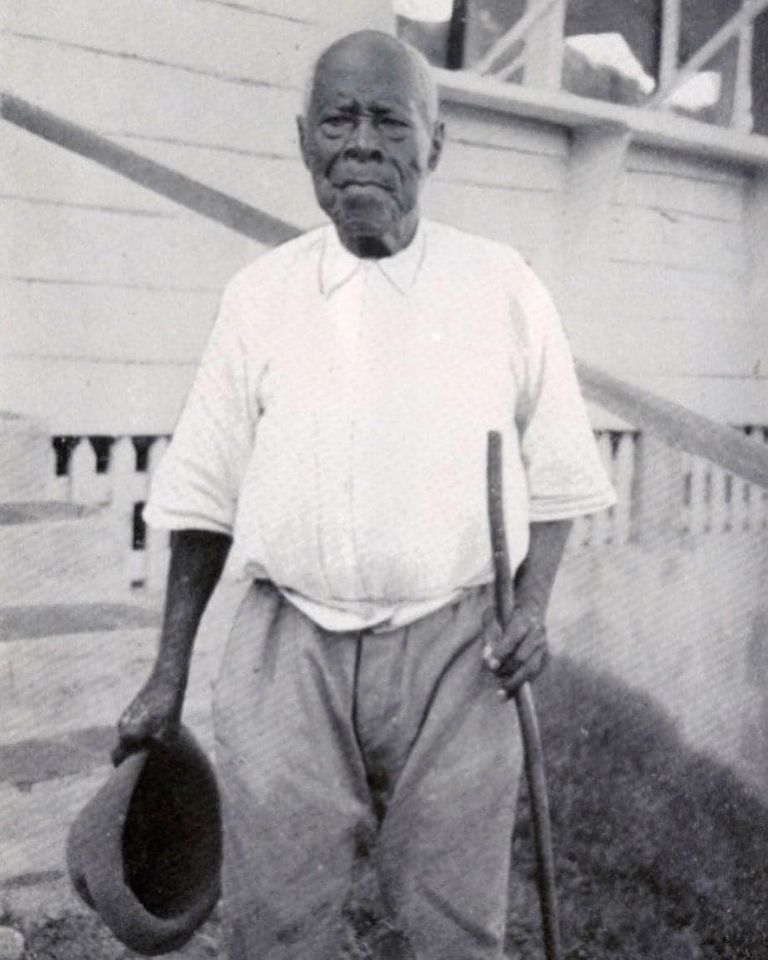

Believed to be one of the longest living persons in Trinidad and Tobago, he had been kidnapped into the slave trade in 1850.

Campbell (pictured) was illegally kidnapped by Portuguese slave traders in his home village in the Congo. He was then taken to the coast with other captives, and sent to the Americas on a slave ship. While in transit, a British warship intercepted the vessel and arrested the slave traders. Campbell and others who had been abducted from their homes were sent to St. Helena, an island in the South Atlantic Ocean. They were a few of many enslaved Africans who were removed from slave ships by the British Royal Navy after the Slave Trade Act of 1807 was passed. This Act made the British slave trade illegal, although the trade continued in French, Spanish and Portuguese colonies, and in parts of the Americas. Beginning in 1810, the British established treaties that allowed them to use their naval vessels to patrol the West Africa coast and the Caribbean Sea, stopping and searching ships of other nations suspected of participating in the illegal trade. The kidnapped Africans found on these ships in the Caribbean Sea were taken to British Caribbean colonies, while those found on ships off the West African coast were sent to St. Helena or Sierra Leone. Referred to as “recaptives,” or “Liberated Africans,” by the British, many of them were eventually taken to British colonies to fill post-Emancipation labour shortages. Between 1841 and 1861, a total of 6,581 recaptives were sent to Trinidad from Sierra Leone and St. Helena as indentured labourers. Tobago received smaller numbers—292 people from St. Helena in 1851 and 225 during 1862. William “Panchoo” Campbell (pictured) was among those sent to Tobago from St. Helena. He settled in Speyside in 1871 until his death at 115 years of age in December 1938, still bearing the scars of branding on his skin. This photo of William “Panchoo” Campbell is courtesy of "The Book of Trinidad" (2010) by Gérard Besson and Bridget Brereton. This book is part of the National Archives of Trinidad and Tobago Reference Collection. (Source: National Archives of Trinidad & Tobago, July 29, 2022) References: Alford, C. E. R. A Guide Book to Tobago. Trinidad Pub. Co., 1936. Archibald, Douglas. Tobago: Melancholy Isle, Volume III, 1807-1898. Westindiana, 2003. Besson Gérard A., and Bridget Brereton. The Book of Trinidad. Paria Publ., 2010. Travellers throughout the world have always sought hospitable places to rest and eat. The history of the Miller’s Guest House in Tobago goes back many years but has always involved the essential concept of hospitality. Built in 1951 and substantially remodelled to meet modern day standards , the Miller’s Guest House in Tobago still captures the ambiance of a traditional guest house of long ago ,with architecture that evokes the tranquil lifestyle of people the mid-1900s. This family operated guest house was a pioneer establishment in the accommodation sector in Tobago. The first owner Mrs Luvinia Miller , of mixed ethnicity left her home in Barataria to move to Tobago in the 1940s to visit her family members. Luivina who was fondly referred to by many as a Matriarch of Buccoo Point, while in Tobago fell in love with Dusty Miller an inter-island steamship captain and got married. Her family in Tobago , in what seems inconceivable by today’s real estate standards, sold her a plot of land near Buccoo Bay for $50.00 and together with her husband who spent most of his time at sea they built a charming home on the plot of land near the Buccoo beach front. When Winston talks of his mum, the first thing that comes to his mind is her warm spirit, kindness and hospitality. Winston, the Miller’s son says his underlying memory of his mum is of the kitchen. Along with the many baking delights she was a great cook. They say the kitchen is the heart of the home and this was certainly the case with Luvinia. It was here she put her magical culinary skills to work by preparing mouth - watering dishes and delicious breads, cakes and pastries. "She always did make time to put good food on the table, even when there wasn't a lot of money to prepare it," Winston said. Dunstan and Luvinia soon started welcoming and entertaining guests at their charming house. Dustan while on shore leave would often invite his colleagues on ship to have a meal prepared by his wife and offer them a place to spend the night.Now in the 1940s and 50s Tobago was not as developed as it is now .There were no restaurants as obtains today and meals were home- made . It was the era before Tobago was fully developed and tourists to its shores were limited in numbers , the days when backpackers came looking for adventures. In taking about his mom Winston claims that it was his mum’s culinary skills and hospitable nature that served as the catalyst to transform the Miller’s Home into a Guest House. According to Winston, one day a back packer who happened to be passing through Buccoo Point on an island trek , smelt the aroma of food being cooked . He followed the sent of the aroma by tracking along the beach and stopped in front of the Miller’s Home from where the aroma of cooked food was coming . He called out to the owners and when Luvinia came out he said “ Ma , I am hungry and can’t find anything to eat . Would you be kind enough to offer me something to eat ". Being the kind hearted , hospitable person she was Luvinia invited the stranger into her home and provided him with a home cooked meal. After the meal the stranger inquired if she had a spare room he could rest for the night. Luvinia , being the compassionate soul that she was let the weary traveller spend the night in one of her rooms for which he paid a small fee the next morning on his departure. At that time the thought of converting her home into a guest house never entered her mind. But from time to time she did provide accommodation and meals to any traveller, including newly married couples seeking a retreat who wanted to stay at the Miller’s House. After some years of marriage, Dunston her husband became ill and eventually lost his eyesight. Luvinia ‘s world changed drastically since she was now burdened with the responsibility of taking care of her ill husband as well as finding money to buy foodstuff and other basic amenities to upkeep her family . In 1951 realisation dawned on Luvinia that she could make an income by providing accommodations and meals to weary traveller or couples looking for that ideal retreat to spend their vacation.The property was ideally located on the beach front , making it even more attractive to travellers and visitors to the island. Thus the idea of establishing Miller’s Guest House for travellers and visiting tourists from other countries was born in 1951. The newly created guest house soon became a successful enterprise due to the Mrs Miller’s cooking skills, sociable nature and friendly personality. Talk soon spread of the Miller’s Guest House in Tobago that offered delicious home cooked meals and a friendly, relaxed, easy-going, social place to stay. With the passage of time Luvinia soon earned the name as the Matriarch of Buccoo Point. With her small business enterprise, she was able to support herself and her family. Today the manager and owner Winston Pereira, carries on his mother’s legacy. Renovations have been done to the original structure and modern amenities have been added to keep trend with modern times. The Miller’s Guest House even has an onsite restaurant a bar overlooking Buccoo Beach which is named after Luvinia. Efforts have been made by Winston, however, to retain the character of the First Miller’s Guest House. Like his mother ,he too lives in the Guest House with his family and is always around if you need to find out about places to visit in Tobago . He still retains his mother’s legacy of a communal kitchen area where guests are free to prepare their own meal if they so desire .On any given day Winston can be seen interacting with his guests making sure they are comfortable feel right at home. "My mom was amazing,” Winston said "Anyone who came to the Miller’s house was welcomed”. He remembers the warmth and hospitality she showed to anyone that came to her house and now that he is the owner he tries to follow in her footsteps . His mum was his source of inspiration and now he too is creating his own story and legacy of the MILLER’S GUEST HOUSE in Tobago. Photo of Luvinia was shared with me by present owner and manager of Miller’s Guest House Winston Pereira. (Source: Virtual Museum of T&T, August 5, 2002) Taken from Angelo Bissessarsingh's archives

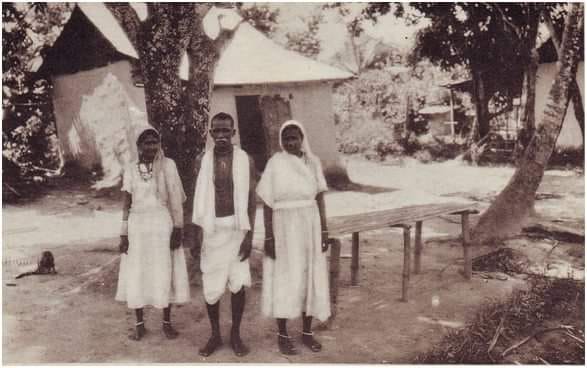

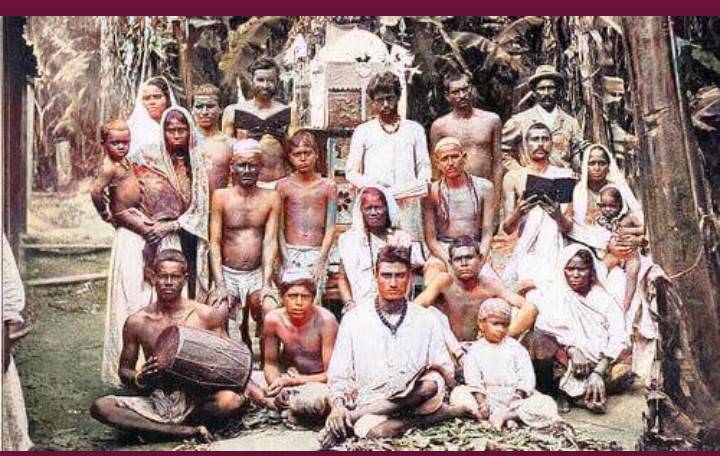

This iconic photo shows a scene that was played out countless times under merciless sun in the canefields of Trinidad during the period of indentureship. Here, the labourers squat on a railway line to take a meal. The looming clouds overhead obscure the light, but this break may have been mid-morning, since cane-cutting often began at 4:00 a.m and earlier to avoid the brunt of the sun. They ate from tin carriers which may have held a bit of roti and aloo, talkaree or maybe dal-bhat (dhal and rice) or khora bhat (pumpkin and rice) . There was no shade in the stubbled canefield so the meal had to be taken in the open sun. A drainage canal in front of the lunching group is visible in the photo and one can probably assume that after consuming the meal, these labourers would have bathed their brows and hands in the muddy trench and then returned to work. (Source: Virtual Museum of TT, May 18, 2023) Author : Historian Angelo Bissessarsingh

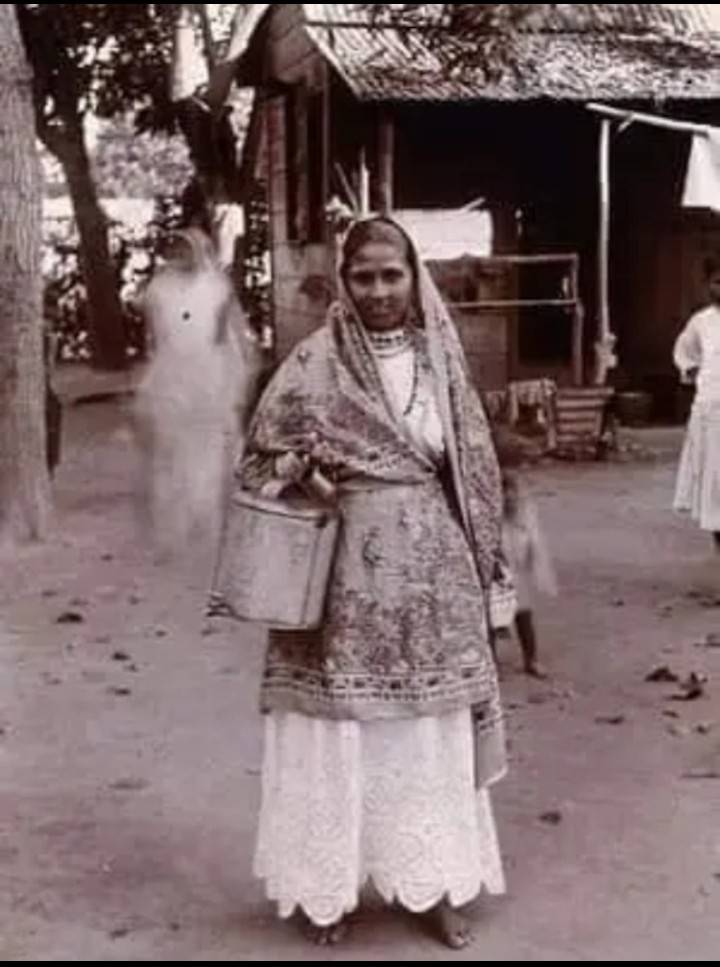

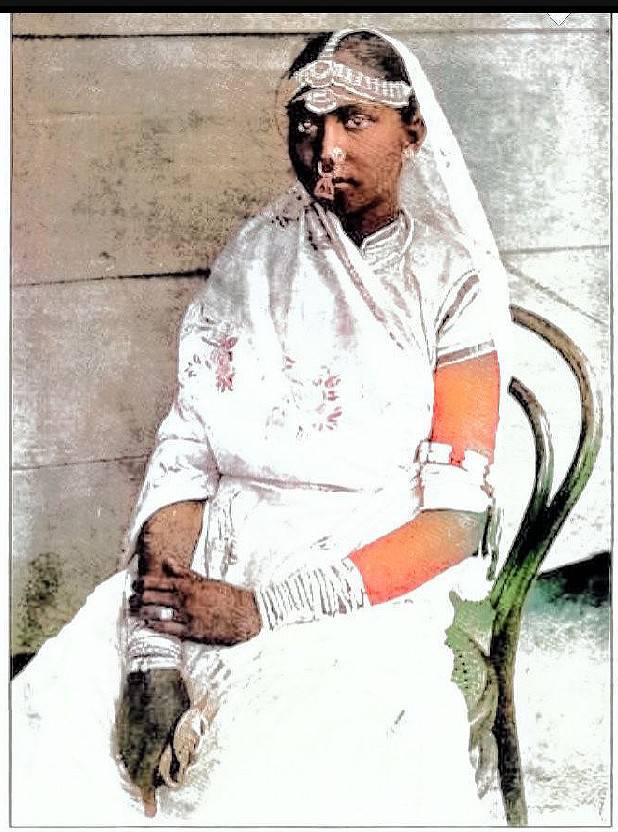

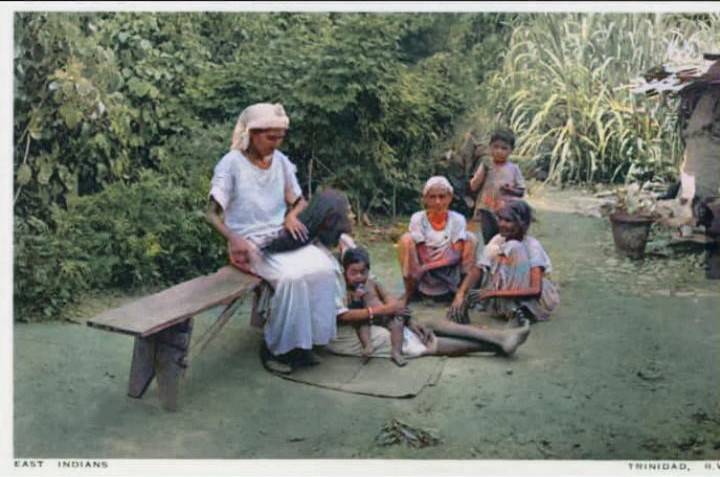

People erroneously assume that upon expiration of their five year indentureship contracts, coolie labourers from India (1845-1917) were automatically handed five acres of land in lieu of a return passage to India as an incentive to stay in the colony. This is not true. The incentive only existed from 1860 and applied only to those who served a full term of the contract. All incentives ceased in 1880 when it was determined that enough had settled in Trinidad to provide a permanent labour force. The Indian who saved from his pittance and bought out his contract received nothing. He and those before 1860, were left to survive on what little they had saved from their wages ($2.50/month for an adult male, $1.75/month for a female, $0.75 for children up to 12). Neither did the incentive consist of land. It was simply five pounds in cash with which the majority purchased crown lands, which after 1870 were available for one pound per acre. Naturally, there were those who for reasons of profligacy or ill-luck ended up as vagrants on the streets of Port-of-Spain. In 1904, it was estimated that as many 140 Indian vagrants slept in Port-of-Spain, most near Columbus Square. From 1849, an official known as the Protector of the Immigrants was appointed to oversee the general welfare of the immigrants, ensuring that they were treated fairly. Often enough, these bureaucrats were corrupt slackers, who took massive bribes from estate owners to not “rock the boat”. The only one who seems to have been a man of energy and conscience was Charles Melville whose father, Henry Melville (and ironically enough, Protector of the Slaves before emancipation) had been a medical doctor and a man of great reputation in the colony. Charles took a dangerous stance in taking his job seriously and arguing with the all-powerful sugar plantocracy for better rights for the Indians. Since the manager of Usine Ste Madeleine was more powerful than the Governor in those days, Melville soon suffered the fate of the conscientious civil servant and was axed. Melville’s successor was Major Comins (1895-1910), an honest soldier and owner of Glenside Estate in Tunapuna. Comins had been an officer in India and was thought to have been the best fit for the job since he understood “the Indian Problem.” Major Comins travelled extensively across the estates, inspecting barracks, and the dreadful living conditions of the Indians on the plantations. His scathing report published in 1902, and revised in 1908 is an indictment on a labour system that was little better than slavery. He was particularly aggrieved over what he saw at Woodford Lodge Estate where Indians were worked longer than stipulated hours, kept on the estate by armed guards, left untreated at a filthy estate hospital and fed on scanty provisions. It was, however, generally understood that as a planter himself, he sought the colonial interests and moderated his views to such an extent as to be a tool of the establishment and not in favour of those he was supposed to protect. The last Protector of the Immigrants was Arnauld De Boissiere in 1927, a playboy and dandy who only held the office for the 400 pounds a year it paid. In Port-of-Spain, Indian vagrants were a lost people, they could not return to India, and even if they could, they would not have been better off. In Trinidad, they were alien, many spoke little or no English, and were considered less than human, both by the middle and upper class of society, the barrackyard dwellers, and the colonial authorities. Most Indian vagrants survived as porters at sixpence a load. The main employers were marchandes (female vendors of edibles), and laundresses who would engaged porters to carry the bundles of soiled clothing collected from the better homes in Woodbrook and St Clair, returning the freshly ironed and starched pieces, neatly folded on a wooden tray, carried by an itinerant porter. Some fortunate displaced Indians found accommodation at the Ariapita Asylum (known as the Poor House) until that facility was closed in 1929. Largely, most begged charity on the streets until death claimed them, their bodies being consigned to the earth of the Pauper’s cemetery in St James, opened in 1900. In Port-of-Spain, Indian vagrants were a lost people, they could not return to India, and even if they could, they would not have been better off. In Trinidad, they were alien, many spoke little or no English, and were considered less than human, both by the middle and upper class of society, the barrack -yard dwellers, and the colonial authorities. Photo Credit : Adrian Coulling. (Source: Virtual Museum of TT, May 22, 2020) Credit to Author , Angelo Bissessarsingh.

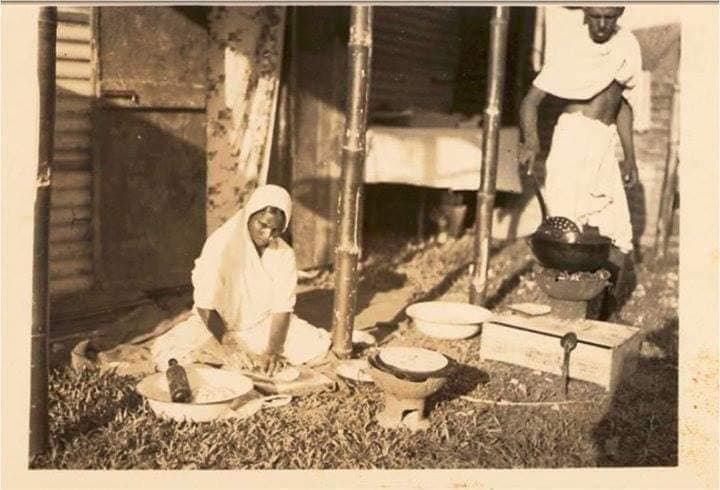

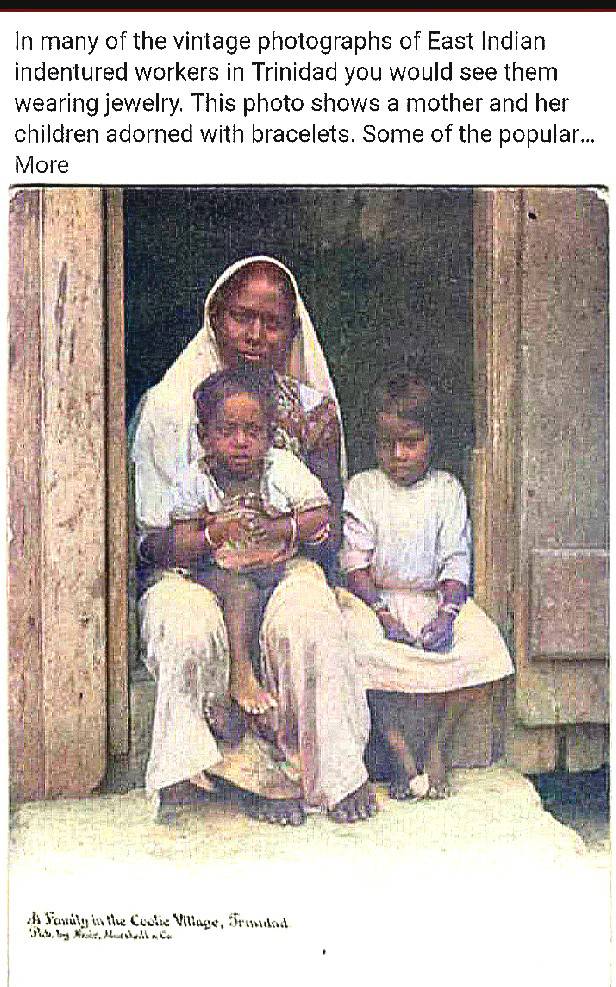

Disclaimer : Article was written by Angelo and in no way intended to offend persons of East Indian descent. Photo credits.. Anthropologists Arthur and Juanita Niehoff. “Cool..e, cool... come for roti, all de roti done.” This was the refrain that haunted many of the formerly indentured Indian immigrants in Trinidad and their descendants from their arrival almost to and including the present day. There is no immigrant story that comes without some painful recollections. It is a testimony however to the spirit of ALL Trinbagonians, that we have managed to grow beyond these recriminations and become a more unified people DESPITE the will of divisive elements such as politicians and pseudo-religious leaders. It seems odd now in a society that counts doubles as a staple food, and where roti has almost epicurean status in some places, that the derision of the Indo-Trinidadians and their food was once commonplace. One of the first articles I wrote for this newspaper back in 2012, was on the roots of Indo-Trinidadian gastronomy which is anchored firmly in the rations which the labourers received during their contracted residences on the sugar plantations of the island. Though the provisions were sometimes augmented or differed according to the estate, the general issue was as Charles Kingsley described it in 1870: “Till the last two years the new comers received their wages entirely in money. But it was found better to give them for the first year (and now for the two first years) part payment in daily rations : a pound of rice, 4 oz. of dholl, a kind of pea, an oz. of coco-nut oil, or ghee, and 2 oz. of sugar to each adult ; and half the same to each child between five and ten years old.” The variations would usually be the addition of a small quantity of saltfish, dried pepper or potatoes. Eked out by provision gardens, often planted with crops brought from India as seeds in the ‘jahaji’ bundles of the labourers, it laid the foundation of a spicy food culture which is as different from anything produced in India today. Those who have dined on authentic Indian dishes will attest to the immense difference from the deliciously creolized creations of Trinidad. Diversification of the Indo-Trinidadian palate came about in the 1880s when many shopkeepers realized what was necessary to attract a clientele from this ethnic group. Wholesalers began to import a variety of spices and curry ground with a ‘sil and loorha’ became more commonplace. Large quantities of ghee, channa (chickpeas). Essentials like mustard oil began to make their appearance at both rural and urban grocers. Nevertheless, Indo-Trinidadian cooking remained an ‘underground’ scene, unknown to most other ethnic groups and rarely tasted outside of the mud huts where it was prepared unless one was invited as a guest. Tempting talkarees, rotis and meetai (sweets) churned out in the aromatic smoke of an earthen chulha (fireplace) were a well-kept secret, not by dint of cultural isolation alone, but also because of a growing sense of shame and self-loathing. Indo-Trinidadian children who attended government schools or schools operated by denominations other than the Canadian Presbyterian Mission to the Indians (CMI) were ridiculed for the lunches they carried, usually sada roti and some sort of bhagi or talkaree. It inculcated a massive inferiority complex which many carried into adulthood. This is well-remembered by persons today and finds its way into Caribbean literature such as the works of Sir V.S Naipaul and Ismith Khan. Well through the 1930s, Indo-Trinidadian concoctions was looked down upon as ‘hog food’ or fit only for the poorest classes. In a calypso sung by the Roaring Lion, he noted the cheapness of the diet by the chorus: “Though depression is in Trinidad, maintaining a wife isn’t very hard, Well you need no ham nor biscuit or bread for there are ways they can be easily fed, like the coolies on bargee, pelauri dhal-bat and dhal-pouri , channa, paratha and the aloo-ke-talkaree” Even doubles at its genesis in the hands of Enamool Deen in Princes Town was viewed as lowly stuff, unfit for consumption by all but rumshop drunks and hungry schoolchildren. In a memoir written by his son, Badru Deen, the struggle to introduce doubles to the urban consumer in San Juan and Port of Spain is well documented. It would be many decades before Trinidad’s most celebrated street food found a place in the national palate. As a fast food, roti was almost non-existent in the towns like Port-of-Spain where it only began to appear in the 1940s during World War II. Roadside roti-stalls were set up with all the necessary utensils, including several coal-pots, churning out dhalpouri with fillings of curried beef (ironic and at once immensely popular), goat, and curried aloo. Chicken a more expensive option. Some rumshops owned by Indians served roti as well. It is a long and stony road that Indo-Trinidadian cuisine has travelled to gain the universal acceptance it enjoys today. (Source: Virtual Museum of TT, May 11, 2023) |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

June 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed